Dread Scott: Performance Art and Radical Action

The following interview is an excerpt from More Art’s book, More Art in the Public Eye, published 2019.

“Fundamental change comes from below. It’s not great leaders, it’s ordinary people who do extraordinary things, and it’s the people who can actually bring people together for fundamental change.”

Dread Scott, in his own words, makes revolutionary art to propel history forward. His performances, installations, videos, and photography frequently engage with the ongoing legacy of racism and oppression in the United States and the audience is often an active element of the art. On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide (2014) featured Scott’s attempt to walk across the Manhattan Bridge Archway while battered by a professionally controlled high-pressure water jet from a fire hose, indirectly referencing the 1963 Civil Rights struggle in Birmingham, Alabama, during which city officials used high-pressure water cannons to disperse non-violent protesters and bystanders in an effort to maintain segregation and legalized discrimination. The piece also reflects on present-day struggles against racism and the tactics used to uphold systemized oppression, as demonstrated by the protests and subsequent militarized police response in Ferguson, Missouri, following the killing of Michael Brown, which took place just two months before Scott’s performance. In the past few weeks, many protesters demonstrating and demanding justice for George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, also killed by police, have been met with tear gas, rubber bullets, and increased police aggression.

“Live performance is important,” Scott said during a 2017 interview with More Art, excerpted below from More Art in the Public Eye. “What people see when somebody is doing something transgressive — like burning money or when somebody is standing up to a fire hose — is something you knew that people had done, yet you didn’t know that people could do.” During the 2014 performance, as Scott approached the fire hose, he at times held his hands up, stumbled, fell, turned his back on the stream, leaned into it, slashed at the water, and continually bared his teeth in response to the pressure and spray. The performance lasted just over twenty minutes, and ended with the exhausted artist standing.

A lot of my work has looked at how the past both sets the stage for the present but also exists in the present in new forms. I do think that in America there’s a lack of historic context and a lot of historic amnesia. Some of it is sort of ignorance that’s [based on the fact that] people haven’t been educated, but part of it is a willful ignorance. So when war happens, it’s like, Well, the bad guys shot us — and well, maybe they did but what did you do the week before that? Looking at how the past sets the stage for the present is actually a really important part of my methodological approach.

But what is important about works like this, On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide, in addition to saying that we are part of a history and that our present is part of and connected to that history, is to ask how do things from the past — both horrors from the past but also radical attempts to be progressive and radical — exist in the present?

Recently I’ve been really trying to look at how people have looked at freedom and how they have tried to get free — how do you make work about that? There’s a really good history of artists that are looking at the horrible things that people have done to each other. There’s not as much history, outside of revolutionary societies, of people actually looking at what is freedom. How do we transform that?

On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide is looking at the fact that it is impossible for people to get free in this country — a country that was founded on slavery and genocide — but people have tried and they’ve made radical change. It was the youth, high-school kids, in Birmingham; that’s mostly who was out in that particular segment of the Civil Rights Movement. They had a belief that legalized discrimination was wrong and they were gonna change it and so they stood up. The piece really connects that past with the present.

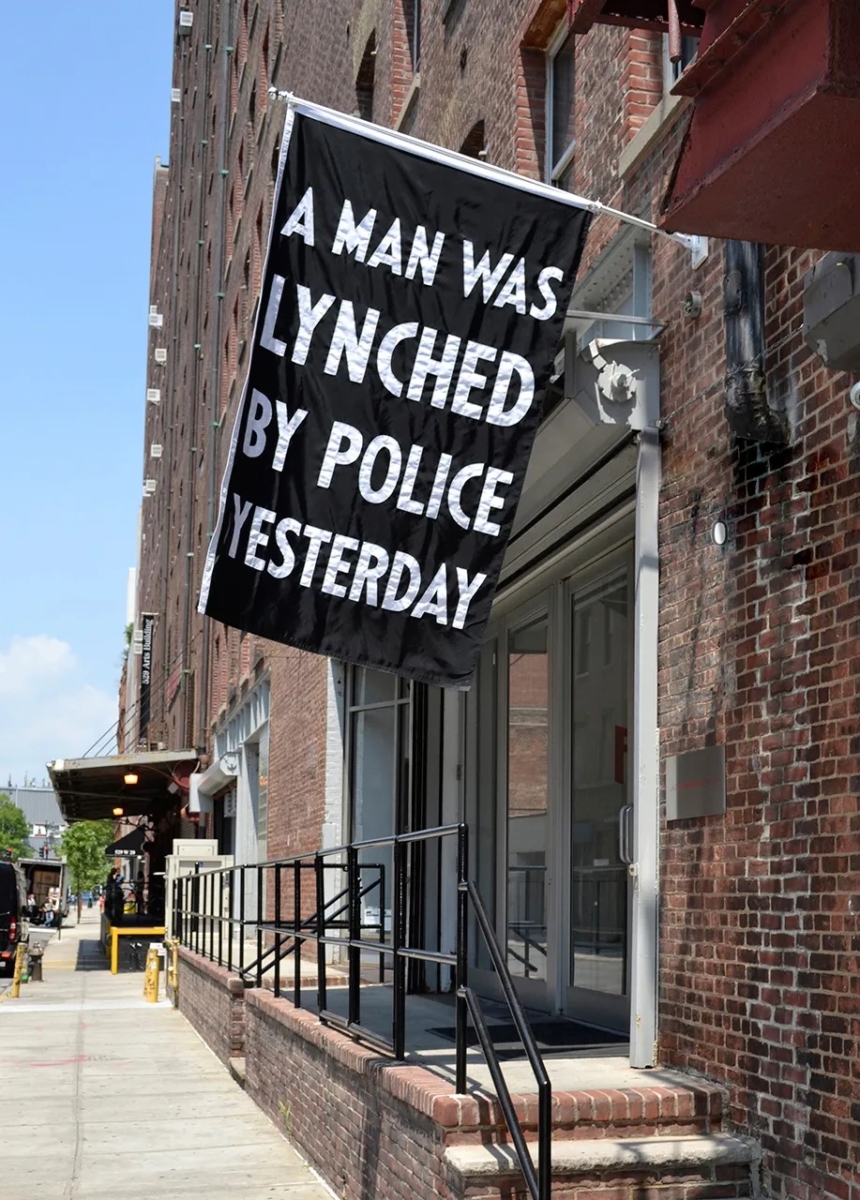

Dread Scott, A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday (2015) — Scott created this banner, hung outside the Jack Shainman Gallery on West 20th Street, in response to the murder of Walter Scott, who was fatally shot eight times in the back by a police officer. It is an update of an iconic flag that the NAACP would fly from their national headquarters window in New York in the 1920s and ’30s the day after a Black person was lynched; the original read “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” and was part of their anti-lynching campaign. Of his piece, Scott writes, “I’m glad for A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday to be part of the growing dissent and ferment as people act to end police terror.” Image courtesy of the artist’s website.

One thing that was kind of coincidental was that the audience for the performance included an entire class from Gotham Academy, a school in Bed-Stuy — a historically poor, historically Black neighborhood — high-school kids who wanted to come see a Dread Scott performance. It’s a performing arts school, but they don’t get to see a lot of live performance. It struck me, when I was performing and when I talked with them later, that all these kids had a deep understanding that they could be the next Mike Brown, that their lives could be ended by a cop, for no reason — for having their hands up, for not having their hands up, for having their hands in their pocket, for running, for not running, for talking back, for not talking back, for playing loud music, for not playing loud music — for anything. They had a deeply ingrained sense that in this system their lives count for absolutely nothing. But most of them didn’t know how they could be the next Freedom Fighter, they didn’t know. And so the performance was trying to engage that question.

For these kids the ’60s is textbooks. The point is not “let’s recreate the ’60s, they were brilliant,” but more that there are lessons to be learned from looking at the ’60s. This performance was really trying to reference this past that you have a vague memory or understanding of, and then embody the present in that. This performance was not just about Birmingham, it was about the broader struggle of people trying to be free from oppression. There is the particular Birmingham, where this government was trying to enforce legalized discrimination and was attacking not only protestors but bystanders. This performance had the understanding of that history, but there weren’t signs of people calling for an end to segregation, there were no chants, there wasn’t groups of people. There was one person. In the ’60s there were a lot of people who were out and it lasted days; this was one 23-minute performance. But it did draw those connections and parallels. It was symbolic but it was rooted in that past. And yes, people can study the past but it wasn’t a call to study per se, it was more an ideological and moral question. Freedom is worth fighting for, but if you do [fight] you may get battered in the process. But then you get back up, you keep coming.

Dread Scott, On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide (2014). CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Project commissioned by More Art. Photo ©2014 Mark Von Holden / Mark Von Holden Photography

I do think I’ve been on the losing side of a lot of social justice struggles. But it’s not important that we lose, it’s important that we fight. I don’t think we’ve reached the end of history. Fundamental change comes from below. It’s not great leaders, it’s ordinary people who do extraordinary things, and it’s the people who can actually bring people together for fundamental change. You can’t do that without the belief that you can do that; it doesn’t mean that you’ll do it just because you have that belief. Many times you’ll be wrong.

We’re sitting here talking in Trump’s America. Trump is a fascist, it’s beyond run-of-the-mill imperialism, he’s reforming society… This is the context in which this conversation is happening, which is a few years after this performance took place. Does art about things like this have anything to do with whether people can drive a regime like that from power and have the vision to say, “We refuse to tolerate this, this is unacceptable and we desire to be free”? In the title On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide, there’s a bit of a conceit there: it says “in a country founded on slavery and genocide.” I don’t think people can actually be free in a society based on exploitation and oppression, with this history. I think people can fight for freedom, I think people can make significant changes, but to actually be free I think we need to get rid of a society that is based on exploiting people.

The piece is a call for people to think about actually having the courage, the tenacity, the vision to resist, even if you might not win a particular battle. It is the just struggle, what needs to be done. I think that one of the ways — and this gets back a bit to the symbolic — that we know this history is largely through photographs, which are black-and-white photographs. There’s this way in which a color photograph, which is the main way that my work is seen, does not actually just reside in the past but comes back and talks to the present and our moment. It’s not about futility, it’s about actually moving forward and bringing these ideas to life as art, but also for people who see the art. We do need to be free and we need people thinking about what we do and what’s worth risking and what’s worth living and, in some cases, dying for.

Dread Scott, On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide (2014). CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Photo by Hrag Vartanian

In some cases I’m willing to expose the audience to the foundations and relations of this society in ways that you can often insulate yourself from. With On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide, it’s like, most people think racism is bad, most people know that Civil Rights demonstrators went through difficult situations in the ’60s, and most people know Black kids get shot by cops — everybody kind of knows that. In this case you were being exposed to a different way you could live, even if you don’t choose to do it at that moment, at that time. You’re like, Wait a minute, why do I accept that 1,100 people are going to be killed by cops every year in America? Why do I accept that that’s disproportionally Black and Latino people?

I do think that live performance takes an audience places, because it’s both live and not theater, and there is a reality that’s there. I’m sure most people seeing the performance didn’t think I’d actually be maimed, but you didn’t quite know. The phenomenological experience of seeing someone blasted with a fire hose is like, Will he be ok? how long will this go on? I’m with him, I’m going on that journey, I hope he’s not hurt… For me as a performance artist, in that case, it was — transcendent is not the right word — very emotional. I was very much drawing on the energy, particularly of the youth from the Bed-Stuy school. It was really a connection with them; it was being performed for them. I was doing things that I didn’t know I would do in advance or know how they would affect me. I was trying to channel the spirit of the people who stood up to water cannons in the 1960s but also, Mike Brown had recently been killed and I knew that was there in the room (or on the bridge). The live performance is important. What people see when somebody is doing something transgressive — like burning money¹ or when somebody is standing up to a fire hose — is something you knew that people had done, yet you didn’t know that people could do. It actually is powerful for me to be challenging that. People are both being exposed to that but are also able to be inspired by that.

1. Money to Burn is a performance by Scott that was enacted on Wall Street in 2010. Starting with $250, Scott burned money — singles, fives, tens, and twenties, one bill at a time — while encouraging traders and others on the street to join him with their own money.

This excerpt is from More Art in the Public Eye, distributed by Duke University Press, now available in paperback and ebook formats; Micaela Martegani, Jeff Kasper, Emma Drew, editors.

This article was also published on More Art’s Medium site here.