Gentrification is a dirty word that is central to the discourse of New York City’s rapidly changing environment. It’s a major concern for longstanding neighborhoods of working class people. There are different perspectives as to whether gentrification hurts or helps the neighborhood’s vitality, but what should be evident to all are the drastic changes in many a neighborhood’s zoning. Old historic buildings are coming down at a swift pace, and new luxurious glass condominiums are popping up in their wake.

Areas such as SoHo, Chelsea, The Meatpacking District, The Lower East Side in Manhattan, and Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Bushwick, and Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn, have mainly been stripped of their multi-ethnic, working-class legacy and replaced by consumer driven extravagance. Most of the residents who have lived for generations in these neighborhoods can no longer afford the inflated cost of living. While proponents of this change report better quality of life overall –less violent crime, less drugs, better nutrition options, more jobs– they are blatantly ignoring those who had already struggled to create a better life in their longtime neighborhood. Just as they begin to make ends meet developers start buying up as much property as possible and raising rents at a staggering rate. Despite the unfilled promise of “new jobs” and “affordable housing” often included in these developer’s rhetoric, longtime renters have little to no choice but to relocate.

These industrious areas were once a vibrant neighborhood for arts communities as well. Artists move into a neighborhood –plagued by unemployment, gang-violence, and buildings left to decay– establish studios and collective spaces in old lofts, and generally make positive changes to desolate public space. Artists tend to be a developer’s point of entry, and soon after they assemble together and create thriving creative communities, the private sector rushes in and drastically develops the neighborhood. Due to the rapid commercial growth, the prices of studio spaces become extravagantly high and unaffordable to many of the artists who were initially drawn to the large, affordable live-work space. It is easy to point a finger at these artists for spurring this gentrification, but this issue has also led the artistic community to become vocal and participate in collective community organization. Collaborating with the longtime residents, artists have the power to bring about transformative social change.

In the 1990s the artist Rick Lowe solicited the help of local African American artists and transformed an abandoned set of row houses in Houston’s Northern Third Ward neighborhood –one of the oldest African American communities in the city– into houses for low-income families. The project called Project Row Houses incorporates workspaces, offices, and residency spaces for artists, while providing arts education, a community gallery, a park, and low-income housing and commercial space for the community. The Project Row Houses also has residencies designated for young mothers to live and receive support to finish school.

Before he founded Project Row Houses, Rick Lowe was making socio-politically driven art in the form of large paintings but the revelation to move out of the studio and into the community came when a group of local high school students visited his studio. Rick Lowe, quoted in an article by Michael Kimmelman for The New York Times, (“In Houston, Art Is Where the Home Is,” New York Times, December 17, 2006) “I was doing big, billboard-size paintings and cutout sculptures dealing with social issues, and one of the students told me that, sure, the work reflected what was going on in his community, but it wasn’t what the community needed. If I was an artist, he said, why didn’t I come up with some kind of creative solution to issues instead of just telling people like him what they already knew. That was the defining moment that pushed me out of the studio.” A wide-range of artists including Edgar Arceneaux (co-founder of the Watts House Project, a non-profit neighborhood redevelopment organization in Watts.), Andrea Bowers, Sam Durant, Julie Mehretu, and Coco Fusco, have worked on and contributed to the Project Row Houses.

Rick Lowe’s transition from an artist making a socio-political statement from within the art world, to an artist whose making a statement within the community, demonstrates the transformative value contemporary art has in our daily lives. By engaging the community through collaborative artistic projects and arts education, an artist can help form a diverse and all-embracing network of people, hopefully inspiring the growth of a movement where creative practices result in socially engaged action taken by communities.

In Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has unofficially designated a conceptual artist as commissioner of renewal on the South Side. The artist, Theaster Gates, has dual degrees in Urban Planning, and incorporates abandoned buildings and houses as raw material. Gates’Dorchester Projects is one of his most celebrated works, and it is another example of what artists can do to work collaboratively with the community. Gates bought and reshaped abandoned buildings in the South Side’s Grand Crossing neighborhood. In these reframed buildings Gates created cultural institutions for the neighborhood to have access to a library of books and music that he collected from a defunct music store and a failed bookstore. As the project grew, he bought more property, both residential and commercial, and has kept the tenants rent well below market rate. He hopes that his investments in the local community will spur a thriving new South Side. However, with all these positive changes and interest from a wide range of people including philanthropists, politicians, art collectors, there is the possibility of gentrification down the road. It is also possible that his work will inspire others to continue to develop, build, and preserve a creative and affordable neighborhood that is beneficial to longtime residents and artists.

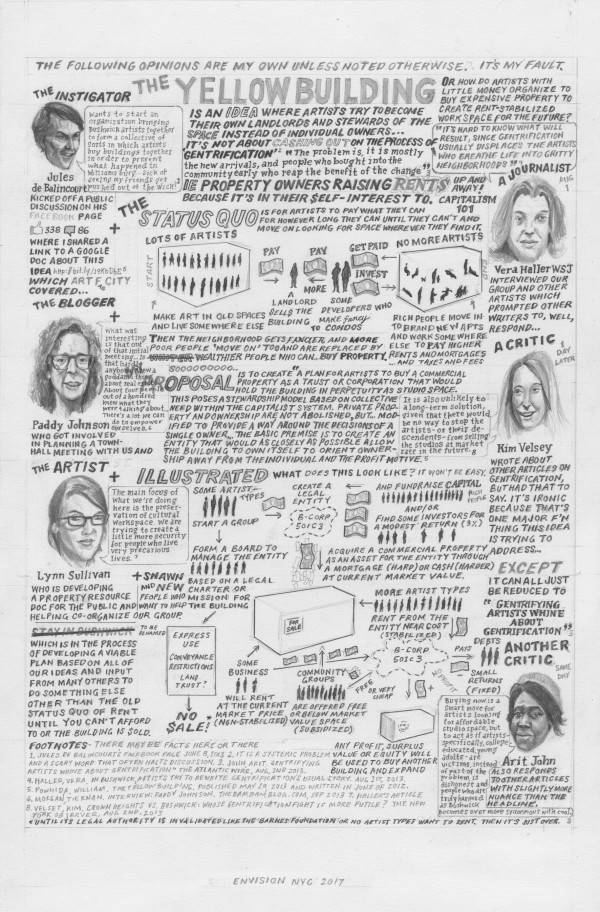

Jules de Balincourt and William Powhida articulated a call for an undertaking by Brooklyn artists slightly similar to the philosophy of Theaster Gates. Powhida is an artist and art critic, and de Balincourt is a painter. Both artists live in Brooklyn and want to create an alternative course to the current neighborhood development. They want to prohibit developers from turning potential studio and loft spaces into overpriced studio apartments, big banks, and shopping malls. They propose that artists collectively purchase large buildings and make them into a permanent artistic space devoid from real estate and private sector influence. The goal is for these neighborhoods to remain a place of uninhibited creative influence while sustaining the history and character of the community.

We commissioned William Powhida to create a project for Envision New York 2017, our web-based public art project. Powhida’s contribution, The Yellow Building presents a plan for artists and other creative workers to buy a commercial property as a trust, foundation, or corporation that would hold the building in perpetuity as studio space. Powhida explains, “This poses a stewardship model based on collective need within the capitalist market system. Private property and ownership are not abolished, but the terms are modified to provide a way around the decision making of an individual owner or developer.”

Is artistic intervention in the community a viable solution to the issues of poverty, public education, housing, food justice, and other pressing social issues? Probably not on its own, that is a problem that needs to be solved by community officials creating public policy beneficial to solving these issues. What artist and community collaboration can and should do is present a visual narrative that is indicative of the social change we all want to see for our current and future generations.

Resources and articles:

The Accidental Playground by Daniel Campo (Fordham University Press. 2013)

“In Houston, Art Is Where the Home Is” Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times, (December 17, 2006)

The Real Estate Artist, by John Colapinto, The New Yorker, (January 20, 2014)

“Ask a Native New Yorker: Gentrification” Gothamist Part 1 and Part 2