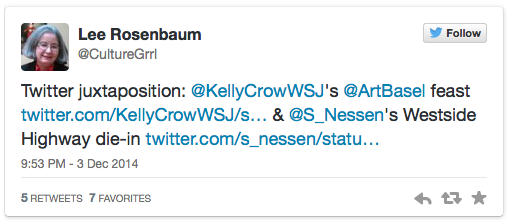

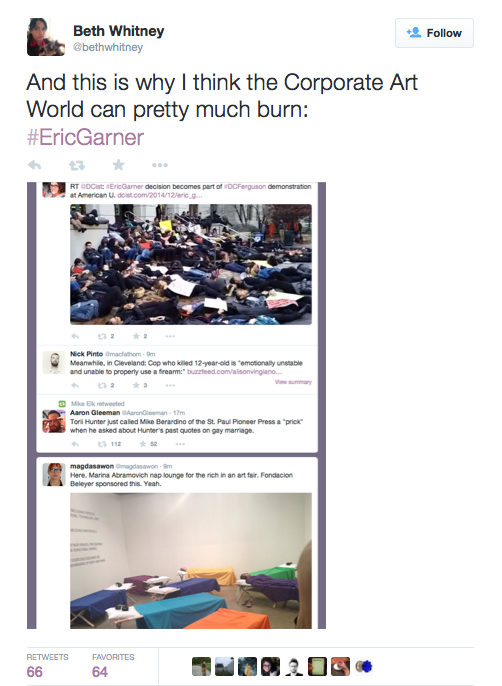

The art world (the commercial side of it) showed its stripes during Art Basel 2014. While the nation (and the world) was protesting the aftermath of the injustices resulting from the grand juries refusal to indict officers who’ve shown excessive force in the deaths of unarmed black men (unfortunately the list of names of black individuals killed at the hands of authoritative figures consistently grows); the art world was spending exuberant amounts of money on fine art objects and reveling at celebrity filled after-parties around the beaches of sunny Miami. Perhaps there is no greater divorce between civil rights and capitalism than Art Basel. For some this was not a novel realization, the art market dominates the art scene where capitalism and cultural trends go hand in hand. However, even for those critical of this reality it was a shocking revelation to see the general indifference to the travesties of justice and the oppression of communities throughout the country.

I cannot speak from experience because I did not attend. However, hearing accounts by colleagues of mine (artists, gallerists, curators, critics, etc.) it would seem as though the art fair existed within a bubble devoid from the crisis on the streets and in the heart of our cities. This eerie disconnect from such a profound current event leaves me to ponder whether contemporary art can have a serious role representing contemporary life within society? Does art that is socially engaged yet also shown at art fairs and brick and mortar commercial spaces lose some credibility because of its association to the ‘capitalism gone wild’ of the art market? Artists have to survive, they don’t (usually) just put their work outside of their studio for the public to view without some form of compensation. As a former owner of a small gallery, I understood that in order for smaller galleries to develop an exciting and sustaining curatorial program they must (begrudgingly or not) take part in whatever art fairs they can afford. Even with moderate participation in art fairs, it is likely that many of these smaller and more experimental spaces will fold because of the rising costs of both their brick and mortar spaces (especially if they’re located in NYC) and the exhibitors fees of the art fairs. When the top tier galleries and those start-ups with substantial backers can play the market far better than anyone else their programs (stable of artists) win.

This is also brings up a great concern about the overall lack of non-white artists represented in major exhibitions and Biennials. The last Whitney Biennial came under criticism for its lack of black artists (and the inclusion of a white performance artist whose persona portrays himself as black). Of the 103 exhibited artists only nine were black. The controversial inclusion of Donnelle Woolford, a fictional artist created by a white artist, further clouded the discourse of art world equality. Throughout the scholarship of art history, African American artists have been poorly accounted and contextualized. When I was sitting in class and we were discussing movements during the course of modernity, I would frequently wonder what black artists were doing at this time? Certainly they must have been as active (at least in their studios) as the (mostly) white men whose slides we’re seeing. Why is it that Abstract Expressionist Norman Lewis is often the only black male included in mainstream discussions of Abstract Expressionism? Artists played an incredible role in Civil Rights and other social movements of the 1960s, yet too often we are focused on the Warhol generation. Art Historians have a large task ahead of them making sense of art’s relationship to culture. Currently we only have fragments of this culture, which is often narrated by the academic influence and the social elite. This has been complicated and muddled further due to the conflation of the aesthetic value of art and the art market value which is more extreme than ever before.

I don’t believe that it is necessary for all the work in galleries to acknowledge and set out to forge a socially engaged connection with the community. That is the mission and a role fulfilled by non-profits like More Art, A Blade of Grass, Laundromat Project, et al. However, it is time that the art market re-evaluates itself because fairs like Art Basel are profiled on a national level (especially with the influx of the top percent of wealth, which to the public at large it may seem like it is the epitome of the contemporary art scene. Furthermore to say that the excess of Art Basel completely trumped the social issues at hand would be a disservice. There was an outstanding amount of people including community activists and artists from the community and beyond, who attended a rally for Eric Garner, shutting down I-95 during a busy stream of Art Basel parties. Artists by nature are largely a political bunch with conscious concerns for humanity. Widespread social change needs to come from everyone participating, and who better to visualize this than artists? Many of these artists have the support of the aforementioned non-profit arts organizations and in some art institutions (most notably the Queens Museum, MoCNA, and The Walker Art Center), but it is clear that this work is not the focus of more mainstream art circles, especially at events like Art Basel which puts the art world on a pedestal for everyone to see.

In the new year we’d like to revamp this blog to be inclusive of the community’s contributions. We will be featuring several guest bloggers both inside and outside of the art world to present a various degree of critical discourse on many of the issues our society faces.

We’d really like to hear your thoughts on this one. Do you agree or disagree? Were you in Miami and did you manage go to the fair and the protests? If so what was your experience balancing the two?

– Adam Zucker

Communications Assistant

adam@moreart.org